Understanding the Connection Between Frailty and Dementia

Why it’s important to look at the whole patient when diagnosing memory loss or dementia due to Alzheimer’s Disease and other causes.

Most of us are probably familiar with the word ‘frail.’ We often use the term to describe older adults who exhibit certain characteristics such as a slow shuffling walk, dependence on a cane, walker or wheelchair, hearing and vision impairment, and general weakness.

As healthy individuals, our bodies are equipped to cope with the onslaught of everyday life with complex physiological processes such as the regulation of heart rate and blood pressure, hormonal rhythms, muscle tone adjustments, and postural control mechanisms. As we age this can begin to change.

The complex nature of frailty

Frailty is an increasingly emphasized concept in medicine and particularly in geriatrics. It can be defined as a recognizable state of increased vulnerability resulting from a decline in function across multiple physiological systems, which compromise a person’s ability to cope with everyday challenges and stressors. Frailty can increase the risk of disability due to brain diseases, but can also be a manifestation of disease progression.

Frailty is a challenging concept. Factors such as depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, agitation, or disinhibition are also often included as signs of frailty but they are also common precursors of memory and other cognitive and behavioral problems in patients with dementia.

Ultimately, what we want to know is whether frailty is an obligatory consequence of aging, or whether it is possible to avoid frailty, and if so, whether that might promote healthy aging, and prevent or at least delay the manifestation and progression of symptoms and disabilities in dementia.

Do you have concerns about your own or your parent’s frailty? Fill out this short questionnaire and review the results with your primary care provider.

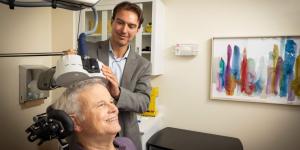

Assessing a patient beyond the brain

Hippocrates reportedly taught his disciples that if they had to choose between learning about the disease a patient had or about the patient who had a disease, they should choose the latter. William Osler, one of the founding fathers of John Hopkins Hospital echoed this admonition: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

Research reveals that a number of frailty factors that we may not usually associate with cognitive decline can indeed have an impact on the development of dementia and reminds us of this important lesson. The risk of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and its prognosis, including the rate and risk of progression to dementia, do not depend solely on the brain, but rather on the entire person.

MCI is broadly considered a precursor to dementia, although not all patients with a diagnosis of MCI go on to develop dementia. When MCI is characterized primarily by memory deficits, the risk of progression to dementia is thought to be particularly high, and the underlying pathology is typically Alzheimer’s disease. However, in assessing the risk for dementia and resulting disability faced by a given patient, it is imperative to go beyond the disease, or even the brain, and consider other aspects of the person’s health and lifestyle.

Taking a holistic approach

A significant body of research reveals the need to consider the personal history, lifestyle, comorbidities, and circumstances of a patient when assessing the risk of developing dementia and efforts to prevent it. At the individual level when confronted with a patient who complains of poor memory or cognitive difficulties, we should not simply complete a careful mental status and a full neurological examination, but also examine:

- Vision and hearing

- Nutrition and low body mass index

- Grip and muscle strength

- Motor function

- Balance

- Gait abnormalities

- Cardiovascular function

- Obstructive sleep apnea, and

- Metabolic and endocrine among other medical conditions.

With a complete picture, we can offer a more detailed prognosis and education about that individual’s disease, along with an effective plan for care that optimizes a patient’s quality of life and hopefully slows the progression of cognitive decline

The role of family and caregivers

Finally, it is worth remembering that an individual’s wellbeing is influenced greatly by their social relations, and specifically, with their caregivers and families. Studies show that older adults with no signs of memory loss who live alone or without close social ties are at increased risk for developing frailty and dementia. Therefore any thorough patient assessment should consider the following:

- Does the patient live alone?

- Do they have adequate family relations or support?

- Have they experienced a disruptive life event such as a move to a different residence?

- Are they going through a period of bereavement?

- Are they functionally disabled?

- What is the extent of the caregiver burden? Does the family and/or caregiver have access to resources that help them cope with their roles?

Treating the whole person along with their family and/or caregivers is paramount

That is why resources like the Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health at Hebrew SeniorLife are so important when looking for memory care.

Our goals include:

- Promoting brain health and cognitive well-being through outreach and educational efforts

- Helping individuals cope with the stress of disease and minimize disability

- Improving diagnostic capabilities, and developing novel interventions that help patients maintain function necessary to reach individualized health and quality of life goals.

Realizing these goals requires a holistic approach to patient care that includes early detection of signs of frailty and appropriate interventions and support to reverse it.

Frailty is not an obligatory consequence of aging. With the appropriate guidance and treatments, we can prevent frailty and promote healthy aging, including reducing the risk of dementia. The Wolk Center aims to provide the support patients and their families need to establish and realize their own personal goals for wellness and quality of life.

To learn more about the Wolk Center for Memory Health and how we can help, call us at 617-363-8600 or contact us online.

Blog Topics

Learn More

Free Guide to Brain Health

Download our free guide, “Optimizing Your Brain Health,” for expert advice on boosting brain health at any age. Explore practical tips and resources from Hebrew SeniorLife’s Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health.

Wolk Center for Memory Health

The Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health at Hebrew SeniorLife provides outpatient memory care services, in person and virtually, for people living with cognitive symptoms — and for their families and caregivers.