Apathy in People with Alzheimer’s or Dementia

Learn about the signs of apathy and why it can be an early sign of cognitive decline.

What is apathy?

Apathy is defined as a feeling of disinterest, when you lack the motivation to do anything or to care about anything around you. It can be a sign of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and mental health conditions.

Adults with dementia and Alzheimer's disease often lose motivation for activities or experiences that used to interest them. They may be uninterested in their environment, and not to respond behaviorally and emotionally to different situations. They may also be indifferent when meeting new people or trying new things. When someone experiences a number of these symptoms, it can be clinically diagnosed as apathy.

Apathy significantly affects the quality of life for the person affected, and increases their caregiver’s distress.

Signs of apathy

Evidence suggests that apathy is more common in older adults with cognitive decline. Initial signs are:

- Lack of interest, motivation, and passion

- Lack of emotional responses and disinterest in relationships

- Low energy levels, which negatively affect the ability to complete daily activities

- Hesitation to take action

- Indifference to things that used to be met with curiosity and interest

- Lack of interest in learning new things

- Lack of interest in new things that are happening

- A tendency to isolate

Older adults with apathy spend more time alone, altering their personal relationships and their ability to carry out daily tasks.

Diagnosing apathy

Apathy is associated with brain changes. It often occurs in the early stages of dementia and persists as the disease progresses, and is one of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia. About 50-70% of people with dementia have apathy, and it’s more common in people with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease than in healthy aging. Evidence suggests that apathy can be an early sign of dementia.

Beyond the social and behavioral impacts, which have a significant impact on a person's life, apathy also has a physical impact. For example, the lack of engagement in activities might decrease strength and balance and slow gait, increasing the risk of falls. Also, having a history of stroke, heart attacks, and other cardiovascular conditions might increase apathy risk.

For a correct diagnosis of apathy, symptoms must last for at least four weeks and include two of the following:

- A loss in goal-directed behavior, resulting in decreased initiative to:

- Participate in social activities

- Begin or respond to a conversation

- Engage in activities of daily life (such as eating, bathing, etc.)

- Loss of purpose, confirmed by at least one of the following symptoms:

- Loss of curiosity

- Loss of spontaneous ideas for new activities

- Loss of spontaneous ideas for ordinary activities

- Loss of emotionality confirmed by either:

- Loss of spontaneous emotion, either as observed or self-reported

- Loss of emotional reactions to positive or negative events

In order to qualify for a clinical diagnoses of apathy, these signs must lead to a significant worsening of quality of life that interferes with daily living activities.

Are apathy and depression the same?

Apathy is not the same as depression. Apathy can be an aspect of depression, but it’s a separate clinical diagnosis.

A person suffering from apathy experiences difficulty taking action on behalf of themselves or others. They feel indifferent about the environment they’re in and don’t respond to what’s happening around them. Even so, no feelings of sadness are present. On the contrary, in older adults affected by depression, the loss of interest is associated with sadness.

Both depression and apathy cause significant impairment in functioning, and a person suffering from either will have trouble taking initiative and lose interest in their daily activities. Still, the conditions cause differences in cognition and emotion: People with apathy are passive, they’re not worried about their health condition, and they don’t complain. They show flattened affect without an emotional response to a situation that generally evokes emotion. Depressed patients feel uncomfortable and actively avoid social situations. They feel sad, hopeless, and guilty.

Here’s a chart comparing the differences and similarities of depression and apathy:

| Depression | Apathy | |

| Daily functioning |

|

|

| Cognition |

|

|

| Emotion |

|

|

How can apathy affect behavior in people with dementia or Alzheimer's disease?

Apathy may cause a lack of interest in many aspects of life. Adults with dementia or Alzheimer's disease may be indifferent when they meet new people or try new things. They also may exhibit no interest in addressing personal concerns and fail to complete routine self-care activities such as bathing, taking essential medications, changing clothes, and keeping a clean living environment.

A person with dementia may not express many emotions through their facial expression, particularly happiness or sadness. Activities or events that generally entertain them may create little to no response. The lack of motivation and the low energy levels may cause a lack of effort and planning in carrying out activities they usually like.

In the long term, apathy may affect a person’s ability to maintain personal relationships, which in turn can increase isolation. When apathy is one of the first signs of dementia – especially when it appears before a formal diagnosis – friends and family members may become frustrated by their loved one’s indifference, and not realize the underlying cause.

Tips for caregivers

If you’re caring for someone with dementia, their lack of interest and unwillingness to engage in everyday life activities can be a source of distress.

It’s common for family members and caregivers to feel overloaded with every minute of their loved one's life. Making some changes in how you approach caring for your loved one can promote their autonomy and independence.

For example, it is essential to minimize your loved one's weaknesses. Reassure and involve them in simple and rewarding activities to maintain their self-esteem.

It's also important to avoid taking your loved one's place in both chores and social activities. Encourage your loved one to do things they used to enjoy, even if they don't feel like doing them. For example:

- Persuade your loved one to go out and spend time with friends. Let their friends know to continue to invite your loved one out, even if they initially say no.

- Propose activities that your loved one used to enjoy. Be persistent and try different suggestions if they don’t take you up on the first one.

- Encourage your loved one to be physically active, either alone or with others. One way to do this is to do it together, like taking a walk after dinner or exploring a new trail.

- Suggest new experiences. Keep them short and achievable so your loved one doesn’t become overwhelmed.

- Reassure your loved one to take action independently and provide positive feedback for what they do.

Most importantly, don’t criticize your loved one or emphasize their struggles or failures. Their inability to carry out their usual activities isn’t caused by laziness, it’s caused by a malfunction in their brain.

Early detection of apathy is important to prevent future cognitive problems in healthy individuals and maintain quality of life in older adults with dementia or Alzheimer's disease. Evidence suggests that as we age, apathy doubles the risk of dementia and therefore requires adequate attention and evaluation over time by family members and caregivers. Someday soon, assessing an individual's apathy level might become a part of the clinician's range of tools to predict future health outcomes.

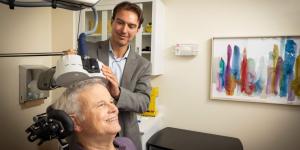

At the Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health at Hebrew SeniorLife, we offer a routine evaluation of brain health, memory problems, and dementia. If you're concerned about signs of apathy in a loved one, we are here for you. We offer comprehensive diagnosis and assessment services for dementia and memory disorders, and can help you put together an individualized plan and resources to maximize the safety and well-being of you or your loved one. We also offer extensive support services for caregivers and families of people with dementia. Interested in learning more? Call us at 617-363-8600 or contact us today.

Blog Topics

Learn More

Free Guide to Brain Health

Download our free guide, “Optimizing Your Brain Health,” for expert advice on boosting brain health at any age. Explore practical tips and resources from Hebrew SeniorLife’s Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health.

Wolk Center for Memory Health

The Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health at Hebrew SeniorLife provides outpatient memory care services, in person and virtually, for people living with cognitive symptoms — and for their families and caregivers.