Dementia, Alzheimer’s and Eyesight: Symptoms and How to Help

Learn how dementia and Alzheimer’s can change vision and what behaviors might result from those vision changes.

Vision loss can become more prevalent as we age. But did you know that vision loss has a connection to dementia? Research has found that older adults with vision problems have a higher prevalence of dementia than those without it.

While experiencing both dementia and vision problems can be disorienting, there are ways for caregivers to modify homes so their loved ones are safer and more comfortable.

Here’s what you should know about the connection between dementia and eyesight:

Visual perception, aging, and cognitive decline

When we look around and see the world, the first step is for light stimuli to enter the eyes and be converted into information that reaches the appropriate regions in the brain. That information is organized, interpreted, and consciously experienced in the brain. The eyes’ receptors continually collect data from the environment, and the brain interprets that information, which affects how we interact with the world. This is known as visual perception, or how the brain makes sense of what the eyes see.

Aging changes our eyes and our brains. Eye diseases like glaucoma, cataracts, or age-related changes in the retina or the macula in the back of the eyes affect the visual information that can reach the brain. Insufficient or incorrect visual information can contribute to the development of cognitive and memory problems such as dementia.

On the other hand, changes in the brain due to dementia or Alzheimer’s disease can affect the way our brains process visual information and alter our perception of the world or our ability to understand it.

When our perception of the world or our ability to understand it is altered, it can lead to anxiety, confusion, or even unusual and incomprehensible behaviors that often leave caregivers disoriented, perplexed, and frustrated.

Visual perception and aging

As we age, we lose the ability to process visual information. Furthermore, medical conditions such as cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and diabetes may aggravate the visual-perceptual difficulties. The significant changes are:

- Blurred vision

- Slower adjustment to light

- Reduced peripheral vision

- A decline in the ability to process distance and three-dimensional objects

Charles Bonnet Syndrome is one condition that may arise with losing vision as we age. It’s characterized by having visual hallucinations that may include:

- Patterns of lines, dots, and/or geometric shapes

- Scenery, such as rivers, volcanoes, or mountains

- Insects, characters, creatures, or animals

- Characters draped in costume from an earlier time

Hallucinations are most commonly reported when people wake up and can persist for a few seconds, minutes, or hours. They may be of various forms, move or be still, and appear in black and white or color.

Do dementia and Alzheimer’s disease change visual perception?

Different types of dementia can damage the visual-perceptual system in diverse ways based on how the disease changes the structure of the brain. Common visual perceptual difficulties are:

- Less sensitivity to variations in the contrast between objects and background

- Diminished ability to detect movement

- Reduced ability to see different colors

- Problems directing or shifting gaze

- Problems with recognizing things and faces

- Reduced sensitivity to depth perception

5 common behaviors associated with vision changes and dementia

Visual perceptual changes influence the person to embrace unusual behaviors that often leave caregivers confused:

- You may witness adults with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease suddenly raising their arms and moving them for seemingly no reason. If we stop and think about the possible cause of the behavior, we might recognize that they are trying to turn off a light shining in their eyes or send away an insect that is actually on the ceiling. The lack of depth perception does not allow them to understand how high the light or the insect is.

- They may suddenly bend over, searching for something around them because they cannot calculate the distance, and the object is actually on the floor.

- They may also attempt to grab objects that appear on television or pick up things depicted in a painting. Failing to do so generates nervousness. They may also process images on TV for real people and become scared.

- An uneven or more marked floor can become an obstacle or a step, and they may be apprehensive or frightened. You may even see them raise their foot, suddenly freeze, and not want to continue.

- They may also have difficulty feeding themselves because they cannot recognize the food on the plate or find their drinking glass.

Tips for caregivers to support vision changes and dementia

If you’re caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, you can make some changes to the environment to support their problems with visual perception. Making the home safe and welcoming can not only help prevent behavioral problems but also promote your loved one’s autonomy and independence.

Modifying the home environment won’t affect the progression of the disease. Still, it can reduce behavioral problems such as agitation, confusion, wandering, aggression, or nervousness and slow down the decline of functional abilities in people with dementia.

In adults with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, the pupils take longer to adjust to light. You can help by turning lights on gradually — for example, a small table lamp before an overhead light — and using adequate lighting to minimize dazzle and shadows.

Wandering is a common behavior that can be dangerous. A person with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia may leave the house without realizing it. In this case, you can work with your loved one’s changes in visual perception to deter them from approaching the front door. Using thick, dark-colored tape or placing a black carpet in front of the door creates limits that persuade adults with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease not to come near.

Use contrasting colors to draw attention to objects. For example, the lack of ability to differentiate between colors makes eating difficult. Evidence suggests that using a bright (e.g., red) plate, utensils, and cups might help your loved one recognize the food and encourage them to eat.

It is also better to stand straight in front of your loved one before speaking. Loss of peripheral vision may cause them to only see things right in front of them. You may disturb them if you approach them from the side or behind.

As we age, getting our eyes checked regularly is essential. That’s true both to prevent cognitive problems in healthy adults and to maintain quality of life in older adults with dementia. A comprehensive eye exam that assesses visual functions such as visual acuity and contrast sensitivity might help diagnose vision problems at their earliest stages.

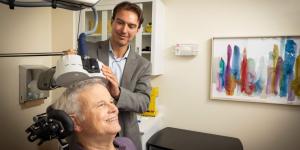

Comprehensive outpatient care for all stages of memory loss

At the Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health, we offer eye exams as part of a routine evaluation of brain health, memory problems, and dementia. If you’re concerned about symptoms of cognitive decline in yourself or a loved one, we are here for you.

We offer comprehensive diagnosis and assessment services and can help you put together an individualized plan and resources to maximize the safety and well-being of you or your loved one. We also offer extensive support services for caregivers and families of people with dementia. Interested in learning more? Call us at 617-363-8600 or contact us today.

Join Our Community: Subscribe to the Hebrew SeniorLife blog for weekly insights on healthy aging and senior living.

Blog Topics

Learn More

Free Guide to Brain Health

Download our free guide, “Optimizing Your Brain Health,” for expert advice on boosting brain health at any age. Explore practical tips and resources from Hebrew SeniorLife’s Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health.

Wolk Center for Memory Health

The Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health at Hebrew SeniorLife provides outpatient memory care services, in person and virtually, for people living with cognitive symptoms — and for their families and caregivers.