The Benefits of a Specific and Early Dementia Diagnosis

An early diagnosis helps slow cognitive decline and a specific diagnosis helps optimize treatment options.

More than 5 million people in the United States alone and over 55 million people worldwide are living with a diagnosis of dementia. Globally, it is the seventh leading cause of death among all diseases, according to the World Health Organization. Societal costs of dementia are estimated at $605 billion per year, and, as the general population grows older, the number of people living with dementia is expected to increase further, with estimates of over 7 million Americans with dementia by 2025 and over 15 million by 2050.

Medical advancements in treating and diagnosing dementia are ongoing, improving the potential for easier and earlier diagnosis and more effective treatments to meet the growing demand. The earlier a patient can receive a dementia diagnosis, the sooner they can start treatment, including reduction of the risk factors that promote the progression of disability. To optimize response to treatment, a number of things are essential:

- Personalize the interventions – treat the person who has the disease, not just the disease.

- Consider the needs of caregivers and loved ones – treat not just the patient, but also the family.

- Empower the patient to plan their future and offer continuing support, not just a check-in every so many months, but rather accompany the patient and their family on the journey of life with dementia.

- Identify the underlying disease causing the symptoms and disability of dementia to ensure the use of appropriate, specific treatments.

These are pillars of the approach to dementia care we take at Hebrew SeniorLife’s Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health.

What is dementia?

The term dementia is used to describe a group of symptoms affecting thinking and memory, mood and behavior, as well as language and social abilities that are severe enough to interfere with daily life. A dementia diagnosis requires three criteria:

- The person must have difficulties in more than one area (or domain) of cognition (for example memory, word finding, decision making, orientation, visual abilities, etc.).

- The problems must be progressive, that is they must get worse over time.

- The problems must affect the person’s ability to take care of daily activities (e.g., driving, managing money, shopping, working, getting dressed, or attending to personal hygiene).

If one has difficulties in more than one area of cognition that have been getting worse (i.e., the first two criteria), but there is no impact on daily activities, then a neurologist may diagnose mild cognitive impairment (MCI), rather than dementia. In about half of all cases, MCI will eventually progress to dementia.

Dementia or MCI can be caused by different diseases or medical events, and depending on the cause, the prognosis is different, the symptoms to expect are different, and the therapeutic needs are different. That is why it is not really enough to establish a diagnosis of dementia or MCI. We must find the specific cause.

What are the causes of dementia?

Common causes of dementia include:

- Alzheimer’s disease: A progressive disease associated with the abnormal build-up of amyloid and tau proteins in and around brain cells, affecting the parts of the brain that control thought, memory, and language. It often begins with memory loss and can lead to loss of the ability to carry on a conversation and respond to the environment. While Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia, it is not the cause of all dementias, and not all people with Alzheimer’s develop dementia. In fact, up to one in four people with Alzheimer’s never show any signs of cognitive problems and never develop dementia or MCI – in them, Alzheimer’s is found only after death.

- Cerebrovascular disease: A disruption in the flow of blood to the brain, which deprives the brain of oxygen and nutrients. This can lead to small blood vessels being blocked, which causes a lesion called a small vessel stroke. The resulting brain damage can affect different parts of the brain and neural networks. Each small vessel stroke is like a road block that forces traffic to find a detour. If only a few roads are blocked, finding a detour is not a big problem, and traffic overall is not really affected. However, when a lot of small vessel strokes accumulate, it’s like having lots of roads blocked, which ultimately really disrupts traffic because detours cannot be easily found. That causes a dementia known as vascular dementia.

- Lewy body disease: A progressive disease caused when clumps of alpha-synuclein protein, known as Lewy bodies, deposit inside of neurons in the brain. Symptoms of Lewy body disease may include spontaneous changes in attention and alertness, recurrent visual hallucinations, alterations of sleep in which one may act out vivid dreams, and slow movement, tremors, or rigidity that resemble Parkinson’s disease.

- Frontotemporal degeneration: A progressive loss of nerve cells in the brain's frontal or temporal lobes, generally caused by the accumulation of a protein called TDP-43. There are different forms of frontotemporal degeneration, but common to all is that the loss can change behavior and personality more prominently and earlier than other forms of dementia. Difficulty producing or comprehending language is another early clinical sign.

There are other causes of dementia, and each has different characteristics, because each affects different parts of the brain. One other important lesson we have learned is that in well over a third of patients, dementia is caused by more than one illness, something we refer to as mixed pathologies. Often, it is a combination of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body disease, and frontotemporal degeneration.

Widespread underdiagnosis of dementia

In addition to the 55 million people worldwide who have been diagnosed with dementia, an estimated 41 million people have dementia but have yet to receive an official diagnosis. People with undiagnosed dementia have limited access to resources available to help them navigate their life with dementia.

Barriers to diagnosis include:

Regional shortages of health care experts, which can limit access to specialized dementia care

- Lack of up-to-date, effective diagnostic tools

- Lack of transportation

- Language barriers

- Insufficient health insurance coverage

- Social stigma

- Mistaken perceptions that dementia and MCI cannot be effectively treated

The role of caregivers in diagnosing dementia

Taking care of a person with dementia often involves a support network, ideally with responsibility spread across multiple family members or other caregivers. Caregivers in the support network can facilitate diagnosis by sharing information with doctors and nurses, as they can offer day-to-day insights that medical staff might not be able to observe. Different caregivers may notice different things, and, if they aren’t sharing their concerns with each other, it’s harder to deliver a consistent, comprehensive list of concerns and observations to medical staff, and diagnosis may be delayed.

In this context, we need to overcome the prevailing social stigma that prevents some people and their families from seeking out appropriate evaluation and receiving a diagnosis in a timely manner. Often people fear raising concerns, as a diagnosis of dementia can be viewed as a hopeless death sentence. But that is not the case. Patients and their families who receive a timely diagnosis may benefit from patient and family counseling services, memory and dementia support groups and caregiver education, and other resources such as those offered by the Wolk Center for Memory Health. Additionally, early and specific diagnosis gives patients and families opportunities for advance planning and interventions that can improve function, slow down and reduce the risk of progression, and minimize disability.

Receiving a diagnosis helps patients, families, and caretakers to plan for the future. Effective care is aided greatly by the patient’s personal support network, so that network needs to be as prepared as possible. Caregivers can set systems in place to help care for their loved ones such as systems to better manage medications. They can also plan for future financial and legal needs such as advance care planning and receive counseling if requested. Other services available are palliative care, dementia education for the person living with dementia, peer-to-peer support groups, and spiritual support.

The importance of early dementia diagnosis

Just as we emphasize a preventative approach to heart health and cancer, we should use the same approach for brain health. It’s logical—a no brainer, if you will—that catching a disease at an early stage is better than waiting until a later stage, and there are some specific reasons with regard to dementia.

Unlike a cold, you don’t catch dementia all at once. Dementia generally starts as mild cognitive impairment. Remember, MCI is defined as a measurable decline in at least one cognitive area—most often memory—that goes beyond the effects of normal aging. However, a person with MCI is still able to perform activities of daily living, including basic ones, such as eating, dressing, and bathing, as well as more complex activities, such as driving, cooking, cleaning, and managing finances. Whereas with dementia, the ability to remember, think, or make decisions is so impaired that it interferes with everyday activities. Delaying and ideally preventing the progression of MCI to dementia is an effective intervention, but it requires a timely diagnosis.

Though there are no cures yet for many causes of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, some medications can help prevent or slow further brain damage. These include a class of medications called cholinesterase inhibitors, which prevent the breakdown of a substance called acetylcholine in the brain. Acetylcholine helps nerve cells communicate with each other and is critical for memory. Slowing its breakdown can help patients regain some lost cognitive abilities. In addition, it appears that starting these medications early and taking them for years can reduce progression of the disease and even delay mortality. Delaying decline in cognitive abilities or daily functioning results in more days of meaningful life people can enjoy with loved ones.

More and more interventions and drugs—such as lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease—are being studied to help patients at the MCI stage. With an earlier diagnosis, patients can potentially be referred to clinical research studies, helping propel research toward a cure while potentially benefiting from the most innovative treatment options.

Additionally, a medical investigation into cognitive health can reveal conditions that mimic early signs of cognitive decline such as reactions to drugs, depression, vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, and alcoholism. Addressing those issues can improve cognitive function. Sleep disruption is particularly important to consider in this context. Obstructive sleep apnea, a common condition associated with snoring and frequent awakenings during the night, is often underdiagnosed and thus not treated, yet it can not only be the cause of memory problems, but also increase the risk of dementia and the severity of the resulting disability.

The importance of a specific dementia diagnosis

Knowing what type of dementia, a patient has is important because different dementias require different, specialized treatments. Different dementias will manifest in different parts of the brain or affect different neurotransmitters (chemical messengers that regulate the nervous system). Treatment plans should be developed only after the care team understands the underlying cause and has a specific diagnosis.

For example, the symptom of behavioral disturbance can be treated in different ways depending on the underlying cause. If the behavioral disturbance is caused by Alzheimer’s disease, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and certain antiepileptics, such as Keppra, can help. If the behavioral disturbance is caused by frontotemporal degeneration, prescribing a neuroleptic might be more helpful.

“Identifying the specific cause of dementia as well as considering the patient’s overall circumstances, lifestyle and goals, are critical to providing the patient and their family an accurate understanding of how their diagnosis will affect them and what therapies are best suited.”

Depending upon the specific form of dementia, a medication may cause more harm than good. For example, cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil are often used to help patients with Alzheimer’s. This class of medications may actually harm frontotemporal dementia patients, increasing impulsivity and disinhibition.

Antipsychotics can help with frontotemporal dementia. They can also help prevent hallucinations that can occur in patients with Parkinson’s disease. However, antipsychotics targeted at behavioral changes can exacerbate the symptoms of Parkinson’s.

Beyond medication, the type of dementia a patient is experiencing determines how the disease will play out, how fast the disease will progress, and which functional abilities will be impacted first. These considerations are all critical to families looking to plan for the future.

How to diagnose dementia and determine underlying causes

Current testing methods to guide a specific dementia diagnosis include comprehensive clinical assessment, such as neuropsychological evaluation, to identify contributing factors; advanced diagnostic imaging testing (such as MRI, DAT scan, PET scan); and biomarker confirmation through the ratio of amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau proteins in cerebral-spinal fluid. All the above can provide insight into the development of the disease and enable differential diagnoses between Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, opening the way for appropriate personalized therapeutic interventions. An interdisciplinary team, including neurology, geriatrics, psychiatry, neuropsychology, and nursing, is often needed in this process.

Additionally, researchers are working to develop a simple, inexpensive, and easily available blood test to identify and differentiate between Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia, which will help a lot more patients get an early and specific diagnosis sooner.

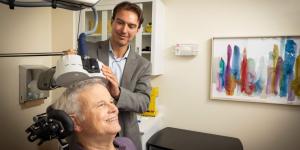

Dementia care in Boston

At the Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health in Boston, we offer diagnostic services and multidisciplinary care for those who are concerned about possible memory loss, for seniors with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, and for family members caring for a loved one with memory loss. We specialize in prevention of cognitive decline, early diagnosis, specific subtype diagnosis, ongoing care for managing dementia, and more.

If you’d like to schedule a visit for a memory assessment, treatment, or family support— including caregiver support groups and individual and family counseling – we’d love to hear from you. Call us at 617-363-8600 or contact the Wolk Center online.

Blog Topics

Learn More

Free Guide to Brain Health

Download our free guide, “Optimizing Your Brain Health,” for expert advice on boosting brain health at any age. Explore practical tips and resources from Hebrew SeniorLife’s Deanna and Sidney Wolk Center for Memory Health.

Long-Term Chronic Care

Hebrew Rehabilitation Center provides person-centered extended medical care in a homelike setting for patients with chronic illness. As a licensed long-term chronic care hospital, we provide higher-level, more comprehensive medical care to older adults than a traditional nursing home.

Coping with Memory Loss

From our Wolk Center for Memory Health to our Adult Day Health program to Assisted Living to Memory Care Assisted Living, we offer a wide range of memory care services and support.